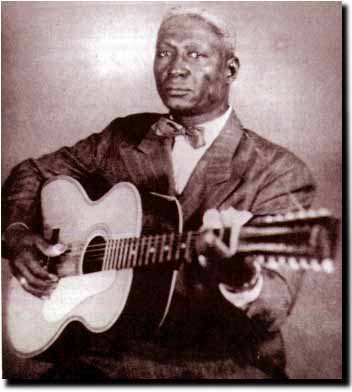

Huddie William Ledbetter (January 20, 1888 – December 6, 1949) was an American folk and blues musician, and multi-instrumentalist, notable for his strong vocals, virtuosity on the twelve-string guitar, and the songbook of folk standards he introduced.

He is best known as Lead Belly. Though many releases list him as "Leadbelly," he spelled it "Lead Belly." This is also the usage on his tombstone,[1][2] as well as of the Lead Belly Foundation.[3] In 1994 the Lead Belly Foundation contacted an authority on the history of popular music, Colin Larkin, editor of the Encyclopedia of Popular Music, to ask if the name "Leadbelly" could be altered to "Lead Belly" in the hope that other authors would follow suit and use the artist's correct appellation.[citation needed]

Although Lead Belly most commonly played the twelve-string, he could also play the piano, mandolin, harmonica, violin, and accordion.[4] In some of his recordings, such as in one of his versions of the folk ballad "John Hardy", he performs on the accordion instead of the guitar. In other recordings he just sings while clapping his hands or stomping his foot.

The topics of Lead Belly's music covered a wide range of subjects, including gospel, blues about women, liquor, prison life, and racism; and folk songs about cowboys, prison, work, sailors, cattle herding, and dancing.Lead Belly was born Huddie William Ledbetter on the Jeter Plantation near Mooringsport, Louisiana in January 1888 or 1889. The date is unclear: the 1900 United States Census lists "Hudy William Ledbetter" as 12 years old, with a birth date of January 1888; the 1910 United States Census and the 1930 United States Census also list his birth year as 1888. However, in April 1942, Ledbetter filled out his World War II draft registration with a birth date of January 23, 1889. His grave marker reflects this date.

He was the younger of two children to Sallie Brown and Wesley Ledbetter, preceded by a sister named Australia. "Huddie" is pronounced "HYEW-dee" or "HUGH-dee."[5] His parents, who had cohabited for several years, married on February 26, 1888. When Huddie was five years old, the family settled in Bowie County, Texas.

By 1903, Huddie was already a "musicianer,"[6] a singer and guitarist of some note. He performed for nearby Shreveport audiences in St. Paul's Bottoms, a notorious red-light district there. He began to develop his own style of music after exposure to a variety of musical influences on Shreveport's Fannin Street, a row of saloons, brothels, and dance halls in the Bottoms.

The 1910 census of Harrison County, Texas, shows Ledbetter, listed as "Hudy," living next door to his parents with his first wife, Aletha "Lethe" Henderson. Seventeen at the time, she had been 15 when married two years earlier. It was there that Ledbetter received his first instrument, an accordion, from his uncle Terrell. By his early 20s, after fathering at least two children, he left home to find his living as a guitarist and occasional laborer.

Influenced by the sinking of the RMS Titanic in April 1912, he wrote the song "The Titanic,"[7] the first composed on the 12-string guitar later to become his signature instrument. Initially played when performing with Blind Lemon Jefferson (1897–1929) in and around Dallas, Texas, the song is about champion African-American boxer Jack Johnson's being denied passage on the Titanic. While Johnson had in fact been denied passage on a ship for being Black, it had not been the Titanic[8] Still, the verse sang: "Jack Johnson tried to get on board. The Captain, he says, 'I ain't haulin' no coal!' Fare thee, Titanic! Fare thee well!" a passage Ledbetter noted he had to leave out when playing in front of white audiences.Ledbetter's volatile temper sometimes led him into trouble with the law. In 1915, he was convicted of carrying a pistol and sentenced to time on the Harrison County chain gang. He escaped, finding work in nearby Bowie County under the assumed name of Walter Boyd. In January 1918 he was imprisoned at the Imperial Farm (now Central Unit)[10] in Sugar Land, Texas, after killing one of his relatives, Will Stafford, in a fight over a woman. It was there he may have first heard the traditional prison song "Midnight Special".[11][page needed] In 1925 he was pardoned and released after writing a song to Governor Pat Morris Neff seeking his freedom, having served the minimum seven years of a 7-to-35-year sentence. In combination with good behavior (including entertaining the guards and fellow prisoners), his appeal to Neff's strong religious beliefs proved sufficient. It was quite a testament to his persuasive powers, as Neff had run for governor on a pledge not to issue pardons (at the time the only recourse for prisoners, since in most Southern prisons there was no provision for parole).[citation needed] According to Charles K. Wolfe and Kip Lornell's book, The Life and Legend of Leadbelly (1999), Neff had regularly brought guests to the prison on Sunday picnics to hear Ledbetter perform.

In 1930 Ledbetter was in Louisiana's Angola Prison Farm after a summary trial for attempted homicide, charged with knifing a white man in a fight. It was there he was "discovered" three years later during a visit by folklorists John Lomax and his then 18-year-old son Alan Lomax.[12] Deeply impressed by Ledbetter's vibrant tenor and extensive repertoire, the Lomaxes recorded him on portable aluminum disc recording equipment for the Library of Congress. They returned with new and better equipment in July of the following year (1934), recording hundreds of his songs. On August 1, Ledbetter was released after having again served almost all of his minimum sentence following a petition the Lomaxes had taken to Louisiana Governor Oscar K. Allen at his urgent request. It was on the other side of a recording of his signature song, "Goodnight Irene."There are several somewhat conflicting stories about how Ledbetter acquired the famous nickname "Lead Belly", though consensus holds it was probably while in prison. Some say his fellow inmates dubbed him "Lead Belly" as a play on his last name and reference to his physical toughness; it is recounted that during his second prison term, another inmate stabbed him in the neck (leaving him with a fearsome scar that he subsequently covered with a bandana), in defense Ledbetter nearly killed his attacker with his own knife.By the time Lead Belly was released from prison the United States was deep in the Great Depression and jobs were very scarce. In September 1934, in need of regular work in order to avoid having his release canceled, Lead Belly met with John A. Lomax and asked him to take him on as a driver. For three months he assisted the 67-year-old in his folk song collecting abroad the South. (Son Alan was ill and did not accompany his father on this trip.)

In December Lead Belly participated in a "smoker" (group sing) at a Modern Language Association meeting at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, where the senior Lomax had a prior lecturing engagement. He was written up in the press as a convict who had sung his way out of prison. On New Year's Day, 1935, the pair arrived in New York City, where Lomax was scheduled to meet with his publisher, Macmillan, about a new collection of folk songs. The newspapers were eager to write about the "singing convict" and Time magazine made one of its first filmed March of Time newsreels about him. Lead Belly attained fame (although not fortune).

The following week, he began recording with ARC, the race records division of Columbia Records, but these recordings achieved little commercial success. Of the over 40 sides he recorded for ARC (intended to be released on their Banner, Melotone, Oriole, Perfect, Romeo and very short-lived Paramount series), only five sides were actually issued. Part of the reason for the poor sales may have been because ARC insisted on releasing only his blues songs rather than the folk songs for which he would later become better known. In any case, Lead Belly continued to struggle financially. Like many performers, what income he made during his lifetime would come from touring, not from record sales. Lead Belly styled himself "King of the 12-string guitar," and despite his use of other instruments like the accordion, the most enduring image of Lead Belly as a performer is wielding his unusually large Stella twelve-string.[16] This guitar had a slightly longer scale length than a standard guitar, slotted tuners, ladder bracing, and a trapeze-style tailpiece to resist bridge lifting.[citation needed]

Lead Belly played with finger picks much of the time, using a thumb pick to provide a walking bass line and occasionally to strum.[citation needed] This technique, combined with low tunings and heavy strings, gives many of his recordings a piano-like sound. Lead Belly's tuning is debated,[by whom?] but appears to be a downtuned variant of standard tuning; more than likely he tuned his guitar strings relative to one another, so that the actual notes shifted as the strings wore. Lead Belly's playing style was popularized by Pete Seeger, who adopted the twelve-string guitar in the 1950s and released an instructional LP and book using Lead Belly as an exemplar of technique.In 1949, Lead Belly had a regular radio broadcast on station WNYC in New York on Sunday nights on Henrietta Yurchenko's show. Later in the year he began his first European tour with a trip to France, but fell ill before its completion, and was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease.[12] His final concert was at the University of Texas at Austin in a tribute to his former mentor, John A. Lomax, who had died the previous year. Martha also performed at that concert, singing spirituals with her husband.

Lead Belly died later that year in New York City, and was buried in the Shiloh Baptist Church cemetery in Mooringsport, 8 miles (13 km) west of Blanchard, in Caddo Parish. He is honored with a life-size statue across from the Caddo Parish Courthouse in Shreveport.

No comments:

Post a Comment